Interested in learning ArcPy? check out this course.

A Heat Map is a way of representing the density or intensity value of point data by assigning a colour gradient to a raster where the cell colour is based on clustering of points or an intensity value. The colour gradient usually ranges from cool/cold colours such as hues of blue, to warmer/hot colours such as yellow, orange and hot red. When mapping the density of points that represent the occurrence of an event, a raster cell is coloured red when many points are in close proximity and blue when points are dispersed (if using the colour range above). Therefore, the higher the concentration of points in an area the greater the ‘heat’ applied to the raster. When mapping intensity, points are assigned an intensity value, the higher the value the hotter the colour assigned to the raster, with lower intensity values assigned cooler colours. Here, we will look at mapping density.

I have created a Python script that creates 250 randomized points in a localised area and 250 in a larger region covering Co. Kildare in Ireland. The script is at the bottom of the post. The output from the script is a GeoJSON file with the point data and also a JavaScript file with the point data. The reason for two files is that GeoJSON coordinates are long, lat while Leaflet points are lat,long. The JavaScript file will be used to create the heat map raster while the GeoJSON file will be used to add the points to the map as a vector.

Unrealistic Scenario: A mad scientist has cloned the Great Irish Elk from the DNA of a carcass and bred 500 of them, the animals grew smarter and escaped. They are beginning to get out of control as they wreak havoc across the land destroying local flora and fauna. Luckily the scientist had the foresight to tag each elk with a GPS tracker. Each point represents the current location of an individual elk. The heat map will aid hunters in focusing their attentions on saving the flowers and critters that dwell amongst them.

Let’s get started and begin to build the HTML file for creating the WebMap. The template below creates a WebMap using Leaflet panned and zoomed to Kildare with an OSM basemap.

Note: Wordpress doesn’t seem to like script or div tags in the code below so if using the code fix the space added to the tags.

Save the code below as a HTML file.

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title> Heatmap with Leaflet </title> <!-- link to leaflet css --> <link rel="stylesheet" href="http://cdn.leafletjs.com/leaflet-0.7.3/leaflet.css" /> <!-- map is full width and height of device --> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, maximum-scale=1.0, user-scalable=no" /> <style> body{ padding: 0; margin: 0; } html, body, #map { height: 100%; } </style> </head> <body> <!-- leaflet js --> < script src="http://cdn.leafletjs.com/leaflet-0.7.2/leaflet.js"></ script> < div id="map"> </ div> < script> var map = L.map('map',{center: [53.15, -6.7], zoom: 10}); // OSM Baselayer L.tileLayer('http://{s}.tile.osm.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png').addTo(map); </ script> </body> </html>

We need to access two plugins, Leaflet.heat and Leaflet.ajax. Download leaflet-heat.js from here and leaflet.ajax.js from here and place them in the same directory as the HTML file. Leaflet.heat allows for the heat map to be generated while Leaflet.ajax enables adding GeoJSON data to the map from an external source. Add the following below the reference to leaflet.js in the <body>. Remember to correct the spaces in the script tags.

< script src="leaflet-heat.js"></ script> < script src="leaflet.ajax.min.js"></ script> < script src="heat_points.js"></ script>

The third script tag above accesses the heat_points.js file created by running the Python script. Make sure that this file is also in the same directory as your HTML file.

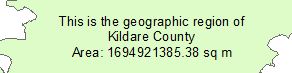

Next we add the boundary of Co. Kildare to the map. The data is stored in an external GeoJSON file. You can access this file here, if following this tutorial save the file to the same directory as your HTML. Before adding the polygon to the map we will define a style for it. Under the line that adds the OSM base layer add the following.

var kildareStyle = { "fillColor": "#CC9933", "color": "#000000", "weight": 2, "fillOpacity": 0.2 };

This will style the Kildare polygon with a translucent brown fill and a black outline. Let’s add the polygon to the map using the Leaflet.ajax plugin…

var kildare = new L.GeoJSON.AJAX('kildare.geojson', {style:kildareStyle}).addTo(map);

Save your HTML and open in a browser. You will notice that the polygon has not been added. This is because the files need to be accessed via a server. There are two things you can do here. Add the files to a hosted server like this map that shows where the tutorial is currently at, or use Python to act as a server for you. Open up the command prompt and set the current working directory to where your files are located. Type in the following to the command prompt and press enter…

python -m SimpleHTTPServer

Open up a browser window and type 127.0.0.1:8000/ followed by the name of your html. For example 127.0.0.1:8000/leaflet_heatmap.html. The map should open with the Kildare GeoJSON polygon styled and added to the map like below.

The map was set up for a desktop so you might need to zoom and pan if using a mobile device. Let’s add the heat layer to the map with one line of code. Place the following under the code that added the Kildare polygon.

var heat = L.heatLayer(heat_points, {radius:12,blur:25,maxZoom:11}).addTo(map);

heat_points in the code above refers to the heat_points variable stored in the heat_points.js file created from the Python script. You can get these points here. This allows us to easily access lat, long as required by Leaflet. Save your file and open in a browser via the Python server. radius is the size of the points, the blur value makes points merge more fluidly, a lower value creates individual points and extreme high values will lose all heat. maxZoom is the zoom level where the map looks best. Other options are minOpacity which is the opacity that the heat will start at, and gradient which allows you to define the colour gradient of the heat map e.g {gradient: {.4:”blue”,.6:”cyan”,.7:”lime”,.8:”yellow”,1:”red”}}. For more information see Chapter 3 from Leaflet.js Essentials from Packt Publishing and the Leaflet.heat page.

There is a high density of elk focused on a location in the west of Kildare indicating that the culling should begin there. Populated areas such as Leixlip, Prosperous, and Kildare town should also be a priority.

To complete the map let’s add the GeoJSON points to the map. The GeoJSON point file can be accessed here. First we define a style, the code below will be a simple black dot for each elk. Place this code under the kildareStyle used to style the Kildare polygon.

var pointStyle = { radius: 2, fillColor: "#000000", color: "#000000", weight: 1, fillOpacity: 1 };

We now use the Leafet.ajax plugin to add the data to the map and the pointToLayer option for a GeoJSON layer. Place the code below under the code that adds the Kildare polygon to the map.

var points = new L.GeoJSON.AJAX('points.geojson', {pointToLayer: function (feature, latlng) { return L.circleMarker(latlng, pointStyle); }}).addTo(map);

Save the HTML and open in your browser (via a server). Click on the map below to open a hosted version of this example in your browser.

Those elks don’t stand a chance unless they learn to shoot lasers out of their antlers.

This was an introduction to creating a density Heat Map with Leaflet.js. Play around with the options; radius, blur, maxZoom etc. to understand how they effect the heatmap layer and use a search engine and the sources below for additional information.

Sources

Leaflet.js Essentials (Packt Publishing)

Calvin Metcalf

Vladimir Agafonkin

Python Script for Coordinate Generation

import random # create a list of 500 points coordinates = [] for coord in range(250): x1 = round(random.uniform(-7.1650,-6.4700),4) y1 = round(random.uniform(52.8320,53.4670),4) x2 = round(random.uniform(-7.0510,-7.0680),4) y2 = round(random.uniform(53.1800,53.1960),4) point1 = [x1,y1] point2 = [x2,y2] coordinates.append(point1) coordinates.append(point2) # open a geojson file to add the points to # change the path to suit your setup f = open("C:/blog/leaflet/points.geojson", "w") # opening bracket f.write('[') count = 1 # add data to the geojson file (formatted) for coord in coordinates: if count == 1: f.write('{\n \ \t"type": "Feature",\n \ \t"geometry": {\n \ \t\t"type": "Point",\n \ \t\t"coordinates": [' + str(coord[0]) + ',' + str(coord[1]) + ']\n \ \t}\n \ }') count = count + 1 else: f.write(',{\n \ \t"type": "Feature",\n \ \t"geometry": {\n \ \t\t"type": "Point",\n \ \t\t"coordinates": [' + str(coord[0]) + ',' + str(coord[1]) + ']\n \ \t}\n \ }') count = count + 1 # closing bracket f.write(']') # close the file f.close() # open a JavaScript file to store coordinates in lat,long # change the path to suit your setup f2 = open("C:/blog/leaflet/heat_points.js", "w") # create a variable f2.write('var heat_points = [') count = 1 # write data to js file for coord in coordinates: if count == 1: f2.write('[' + str(coord[1]) + ',' + str(coord[0]) + ']') count = count + 1 else: f2.write(',[' + str(coord[1]) + ',' + str(coord[0]) + ']') count = count + 1 # closing bracket f2.write(']') # close file f2.close()