This blog post has found a new home at Final Draft Mapping.

(Open Source Geospatial Python)

The ‘What is it?’

The Central Feature is the point that is the shortest distance to all other points in the dataset and thus identifies the most centrally located feature. The Central Feature can be used to find the most accessible feature, for example, the most accessible school to hold a training day for teachers from schools in a given area.

The Formula!

For each feature calculate the total distance to all other features. The feature that has the shortest total distance is the Central Feature.

For Point features the X and Y coordinates of each feature is used, for Polygons the centroid of each feature represents the X and Y coordinate to use, and for Linear features the mid-point of each line is used for the X and Y coordinate

The Code…

from osgeo import ogr from shapely.geometry import MultiLineString from shapely import wkt import numpy as np ## set the driver for the data driver = ogr.GetDriverByName("FileGDB") ## path to the FileGDB gdb = r"C:\Users\Glen B\Documents\my_geodata.gdb" ## open the GDB in write mode (1) ds = driver.Open(gdb, 1) ## input layer input_lyr_name = "Birmingham_Secondary_Schools" ## output layer output_fc = "{0}_central_feature".format(input_lyr_name) ## reference the layer using the layers name if input_lyr_name in [ds.GetLayerByIndex(lyr_name).GetName() for lyr_name in range(ds.GetLayerCount())]: lyr = ds.GetLayerByName(input_lyr_name) print "{0} found in {1}".format(input_lyr_name, gdb) ## delete the output layer if it already exists if output_fc in [ds.GetLayerByIndex(lyr_name).GetName() for lyr_name in range(ds.GetLayerCount())]: ds.DeleteLayer(output_fc) print "Deleting: {0}".format(output_fc) ## for each point or polygon in the layer ## get the x and y value of the centroid ## and add them into a numpy array try: first_feat = lyr.GetFeature(1) if first_feat.geometry().GetGeometryName() in ["POINT", "MULTIPOINT", "POLYGON", "MULTIPOLYGON"]: xy_arr = np.ndarray((len(lyr), 2), dtype=np.float) for i, pt in enumerate(lyr): ft_geom = pt.geometry() xy_arr[i] = (ft_geom.Centroid().GetX(), ft_geom.Centroid().GetY()) ## for linear features we get the midpoint of a line elif first_feat.geometry().GetGeometryName() in ["LINESTRING", "MULTILINESTRING"]: xy_arr = np.ndarray((len(lyr), 2), dtype=np.float) for i, ln in enumerate(lyr): line_geom = ln.geometry().ExportToWkt() shapely_line = MultiLineString(wkt.loads(line_geom)) midpoint = shapely_line.interpolate(shapely_line.length/2) xy_arr[i] = (midpoint.x, midpoint.y) ## exit gracefully if unknown geometry or input contains no geometry except Exception: print "Unknown Geometry for {0}".format(input_lyr_name) ## construct NxN array, this will be the distance matrix pt_dist_arr = np.ndarray((len(xy_arr), len(xy_arr)), dtype=np.float) ## fill the distance array for i, a in enumerate(xy_arr): for j, b in enumerate(xy_arr): pt_dist_arr[i,j] = np.linalg.norm(a-b) ## sum distances for each point summed_distances = np.sum(pt_dist_arr, axis=0) ## index of point with minimum summed distances index_central_feat = np.argmin(summed_distances) ## position of the point with min distance central_x, central_y = xy_arr[index_central_feat] print "Central Feature Coords: {0}, {1}".format(central_x, central_y) ## create a new point layer with the same spatial ref as lyr out_lyr = ds.CreateLayer(output_fc, lyr.GetSpatialRef(), ogr.wkbPoint) ## define and create new fields x_fld = ogr.FieldDefn("X", ogr.OFTReal) y_fld = ogr.FieldDefn("Y", ogr.OFTReal) out_lyr.CreateField(x_fld) out_lyr.CreateField(y_fld) ## create a new point for the mean center pnt = ogr.Geometry(ogr.wkbPoint) pnt.AddPoint(central_x, central_y) ## add the mean center to the new layer feat_dfn = out_lyr.GetLayerDefn() feat = ogr.Feature(feat_dfn) feat.SetGeometry(pnt) feat.SetField("X", central_x) feat.SetField("Y", central_y) out_lyr.CreateFeature(feat) print "Created: {0}".format(output_fc) ## free up resources del ds, lyr, first_feat, feat, out_lyr

I’d like to give credit to Logan Byers from GIS StackExchange who aided in speeding up the computational time using NumPy and for forcing me to begin learning the wonders of NumPy.

At the moment this is significantly slower that performing the same process with ArcGIS for 20,000+ features, but more rapid for a lower amount. 1,000 features processed in 3 seconds.

The Example:

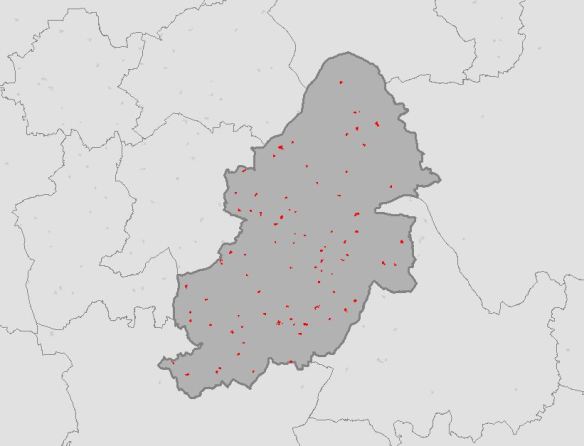

I downloaded vector data that contains polygons for schools from OS Open Map – Local that covered the West Midlands. I also downloaded OS Boundary Line data. Using Python and GDAL/OGR I extracted secondary schools from the data for Birmingham. Everything was now in place to find the Central Feature of all Secondary Schools for Birmingham. (see The Other Scripts section at the bottom of this post for processing the data)

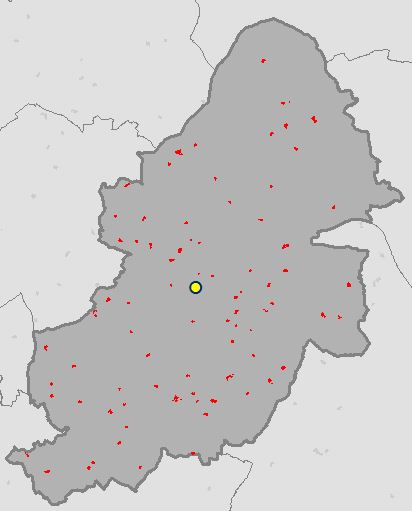

Running the script from The Code section above calculates the coordinates of the Central Feature for all Secondary Schools and creates a point feature class in the File GDB.

OSGP Central Feature: 407726.185, 287215.1

ArcGIS Central Feature: 407726.185, 287215.1

What’s Next?

Median Center (link will be updated once post is complete)

Also see…

The Resources:

ESRI Guide to GIS Volume 2: Chapter 2 (I highly recommend this book)

see book review here.

Setting up GDAL/OGR with FileGDB Driver for Python on Windows

< The Other Scripts >

Birmingham Secondary Schools

from osgeo import ogr import os ## necessary drivers shp_driver = ogr.GetDriverByName("ESRI Shapefile") gdb_driver = ogr.GetDriverByName("FileGDB") ## input boundary shapefile and file reference file gdb shapefile = r"C:\Users\Glen B\Documents\Schools\Data\GB\district_borough_unitary_region.shp" gdb = r"C:\Users\Glen B\Documents\my_geodata.gdb" shp_ds = shp_driver.Open(shapefile, 0) gdb_ds = gdb_driver.Open(gdb, 1) ## filter boundary to just Birmingham shp_layer = shp_ds.GetLayer(0) shp_layer.SetAttributeFilter("NAME = 'Birmingham District (B)'") ## name the output output_fc = "Birmingham_Secondary_Schools" ## if the output feature class already exists then delete it if output_fc in [gdb_ds.GetLayerByIndex(lyr_name).GetName() for lyr_name in range(gdb_ds.GetLayerCount())]: gdb_ds.DeleteLayer(output_fc) print "Deleting: {0}".format(output_fc) ## create the output feature class out_lyr = gdb_ds.CreateLayer(output_fc, shp_layer.GetSpatialRef(), ogr.wkbPolygon) ## the folder that contains the data to extract Secondary Schools from root_folder = r"C:\Users\Glen B\Documents\Schools\Vector\data" ## traverse through the folders and find ImportantBuildings files ## copy only those that intersect the Birmingham region ## transfer across attributes count = 1 for root,dirs,files in os.walk(root_folder): for filename in files: if filename.endswith("ImportantBuilding.shp") and filename[0:2] in ["SP", "SO", "SJ", "SK"]: shp_path = "{0}\\{1}".format(root, filename) schools_ds = shp_driver.Open(shp_path, 0) schools_lyr = schools_ds.GetLayer(0) schools_lyr.SetAttributeFilter("CLASSIFICA = 'Secondary Education'") lyr_def = schools_lyr.GetLayerDefn() if count == 1: for i in range(lyr_def.GetFieldCount()): out_lyr.CreateField(lyr_def.GetFieldDefn(i)) count += 1 shp_layer.ResetReading() for shp_feat in shp_layer: birm_geom = shp_feat.GetGeometryRef() for school_feat in schools_lyr: school_geom = school_feat.GetGeometryRef() if school_geom.Intersects(birm_geom): feat_dfn = out_lyr.GetLayerDefn() feat = ogr.Feature(feat_dfn) feat.SetGeometry(school_geom) for i in range(lyr_def.GetFieldCount()): feat.SetField(lyr_def.GetFieldDefn(i).GetNameRef(), school_feat.GetField(i)) out_lyr.CreateFeature(feat) feat.Destroy() del shp_ds, shp_layer, gdb_ds

The Usual 🙂

As always please feel free to comment to help make the code more efficient, highlight errors, or let me know if this was of any use to you.