Interested in learning ArcPy? check out this course.

I recently sat an interview test where I had to use labelling in ArcGIS Desktop without the aid of the internet or notes for guidance. I must admit I was pretty stumped when it came to formatting labels beyond using the GUI (Labels tab in the Layer Properties) and stepping into the world of expressions, so I decided to rectify this and explore the options. ESRI maintain a fantastic help resource that can be found at here (for 10.2), where you can find what you need to get started. The following examples are some neat ways you can format labels using tags and expressions. They’re quite basic but act as a foundation to build upon.

Open the Layer Properties of the layer you wish to label and switch to the Labels tab. Click on the Expression… button to open the Label Expression window. Switch the Parser at the bottom of the window to Python.

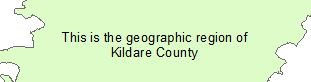

In this first example I will simply concatenate a string with a attribute (also a string), the custom string will be placed on the first line of the label and the attribute of the county name placed on the second. This is achieved with the following…

"This is the geographic region of\n" + [COUNTYNAME]

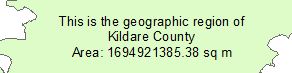

[COUNTYNAME] represents the field names COUNTYNAME in the attribute table of the data I am working with. Next we will concatenate the area on a new line and round the decimal places to two. We cast the area to a string so the concatenation can be preformed.

[COUNTYNAME] represents the field names COUNTYNAME in the attribute table of the data I am working with. Next we will concatenate the area on a new line and round the decimal places to two. We cast the area to a string so the concatenation can be preformed.

"This is the geographic region of\n" + [COUNTYNAME] + "\nArea: " + str(round(float([Shape_Area]),2)) + " sq m"

Next we force labels to be presented in upper case text. The Advanced checkbox must be checked to create multiline expressions. You could also replace upper with lower in the below code snippet to force text to be lower case, or replace with title to capitalize the first letter in each word (proper case).

Next we force labels to be presented in upper case text. The Advanced checkbox must be checked to create multiline expressions. You could also replace upper with lower in the below code snippet to force text to be lower case, or replace with title to capitalize the first letter in each word (proper case).

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME]):

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper()

return label

Stack text on new lines by using replace. The expression below replaces spaces in the COUNTYNAME attribute with n which forces text after a space onto a new line and removes the space.

Stack text on new lines by using replace. The expression below replaces spaces in the COUNTYNAME attribute with n which forces text after a space onto a new line and removes the space.

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME]):

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper().replace(" ", "\n")

return label

Lets make the text bold by using format tags. Each tag has an opening < > and closing </ > tag.

Lets make the text bold by using format tags. Each tag has an opening < > and closing </ > tag.

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME]):

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper().replace(" ", "\n")

return "<BOL>" + label + "</BOL>"

…and then add some colour. Missing RGB values are assumed to be 0.

…and then add some colour. Missing RGB values are assumed to be 0.

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME]):

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper().replace(" ", "\n")

return "<BOL><CLR red='255'>" + label + "</CLR></BOL>"

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME]):

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper().replace(" ", "\n")

return "<BOL><CLR red='125' green='105' blue='190'>" + label + "</CLR></BOL>"

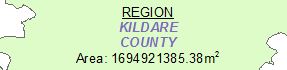

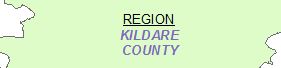

…and italics and an underline…

…and italics and an underline…

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME]):

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper().replace(" ", "\n")

return "<UND>" + "REGIONn" + "</UND>" + "<BOL><ITA><CLR red='125' green='105' blue='190'>" + label + "</CLR></ITA></BOL>"

We’ll throw back in the area and format sq m with a superscripted 2 instead…(use SUB if you need to subscript text)

We’ll throw back in the area and format sq m with a superscripted 2 instead…(use SUB if you need to subscript text)

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME], [Shape_Area]):

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper().replace(" ", "\n")

area = str(round(float([Shape_Area]),2))

return "<UND>" + "REGIONn" + "</UND>" + "<BOL><ITA><CLR red='125' green='105' blue='190'>" + label + "</CLR></ITA></BOL>" + "nArea: " + area + "m" + "<SUP>" + "2" + "</SUP>"

Other format tags are <ACP> for all capitals, <SCP> for small capitals, <CHR spacing = ‘200’> for character spacing or <CHR width = ‘150’> for character width, <WRD spacing = ‘200’> for word spacing and <LIN leading = ’25’> for line leading.

Style labels based on attributes. If the area is greater than 1,000,000,000 sq m the label will be styled like the figure above with a colour, if not it will remain black.

def FindLabel ([COUNTYNAME], [Shape_Area]):

area = str(round(float([Shape_Area]),2))

label = [COUNTYNAME]

label = label.upper().replace(" ", "\n")

if float([Shape_Area]) > 1000000000:

return "<UND>" + "REGIONn" + "</UND>" + "<BOL><ITA><CLR red='125' green='105' blue='190'>" + label + "</CLR></ITA></BOL>" + "nArea: " + area + "m" + "<SUP>" + "2" + "</SUP>"

else:

return "<UND>" + "REGIONn" + "</UND>" + "<BOL><ITA>" + label + "</ITA></BOL>" + "nArea: " + area + "m" + "<SUP>" + "2" + "</SUP>"

This has just been a quick intro into using expression and format tags for labelling. The Information was found in the online ArcGIS Help that can be found here.

This has just been a quick intro into using expression and format tags for labelling. The Information was found in the online ArcGIS Help that can be found here.